COVID-19 Diagnostic:

a game-changer

Who has been infected with COVID-19, and may not even know it?

Answering this critical question is what drives Burnet’s Global Diagnostic Development Group in developing a game-changing, rapid, point-of-care test that could become a vital tool in the management of COVID-19 globally.

Associate Professor David Anderson can recall precisely when he found out the first prototypes of a rapid point-of-care (RPOC) test for COVID-19 that he and his team had been developing, were likely to work.

It was 17 April 2020, his birthday, and the research breakthrough was a real cause for celebration.

Australia was in its first COVID-19 lockdown at the time, and as head of Burnet’s Global Health Diagnostics Development Group, Associate Professor Anderson was focused on finding new diagnostic tools to identify people who had been infected with the virus, many without even knowing it but still having potential to spread the infection.

“Once the test is working a little bit, then you can systematically improve it,” he said of the milestone, just one of many achieved in his 30 years of research discovery at Burnet.

Burnet's Global Health Diagnostics Group: Huy Van, Dr Fan Li and Associate Professor David Anderson

Burnet's Global Health Diagnostics Group: Huy Van, Dr Fan Li and Associate Professor David Anderson

His extensive body of work includes an RPOC test for hepatitis E in the 1990s that was far superior to existing tests, through to the VISITECT® CD4 Advanced Disease Test, which recently achieved World Health Organization pre-qualification.

This test measures CD4 T cell levels in HIV-positive patients to determine whether they should be treated with antiretroviral drugs. Other work includes RPOC tests for active syphilis, liver disease and liver cirrhosis, and current research on new diagnostics for sepsis and measles.

“We learned a lot along that pathway about how to develop different reagents, and we developed some other proprietary technology. We got a really good understanding of how lateral flow tests, point-of-care tests, can work,” Associate Professor Anderson said.

With the COVID-19 prototype in hand, the aim is to put to market a product that could be a game-changer because of its accuracy – in the order of 99 percent – far higher than the 91-95 percent accuracy of existing RPOC tests.

WHAT SETS IT APART?

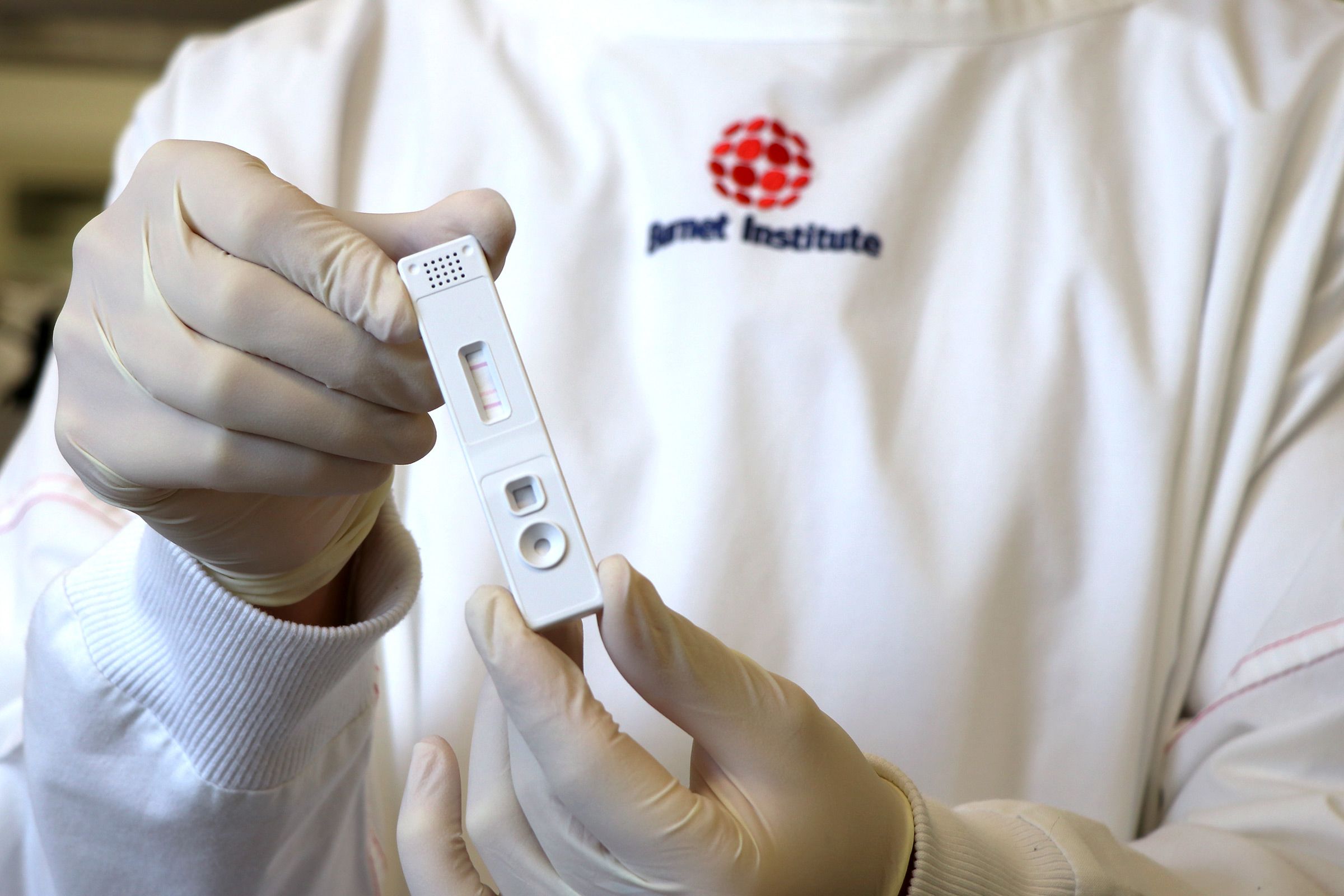

What distinguishes Burnet’s finger-prick blood sample diagnostic from the rest is a patented process to test for dimeric IgA, one of the antibodies the body makes in response to COVID-19, to indicate current or recent infection.

Other RPOC tests look for a different antibody, IgM, which is often cross-reactive to other viruses including many common cold viruses, which leads to a high proportion of false positive results.

Testing for dimeric IgA, Associate Professor Anderson said, was a “pre-COVID idea” his team has been working with since a PhD student, Khayriyyah Mohd Hanafiah, showed it could be useful around eight years ago.

“We now have all of the reagents dried down onto what looks exactly like a pregnancy test, and you just add patient blood and it goes through the device and gives you the colour reaction if there’s antibodies present against the virus,” he said.

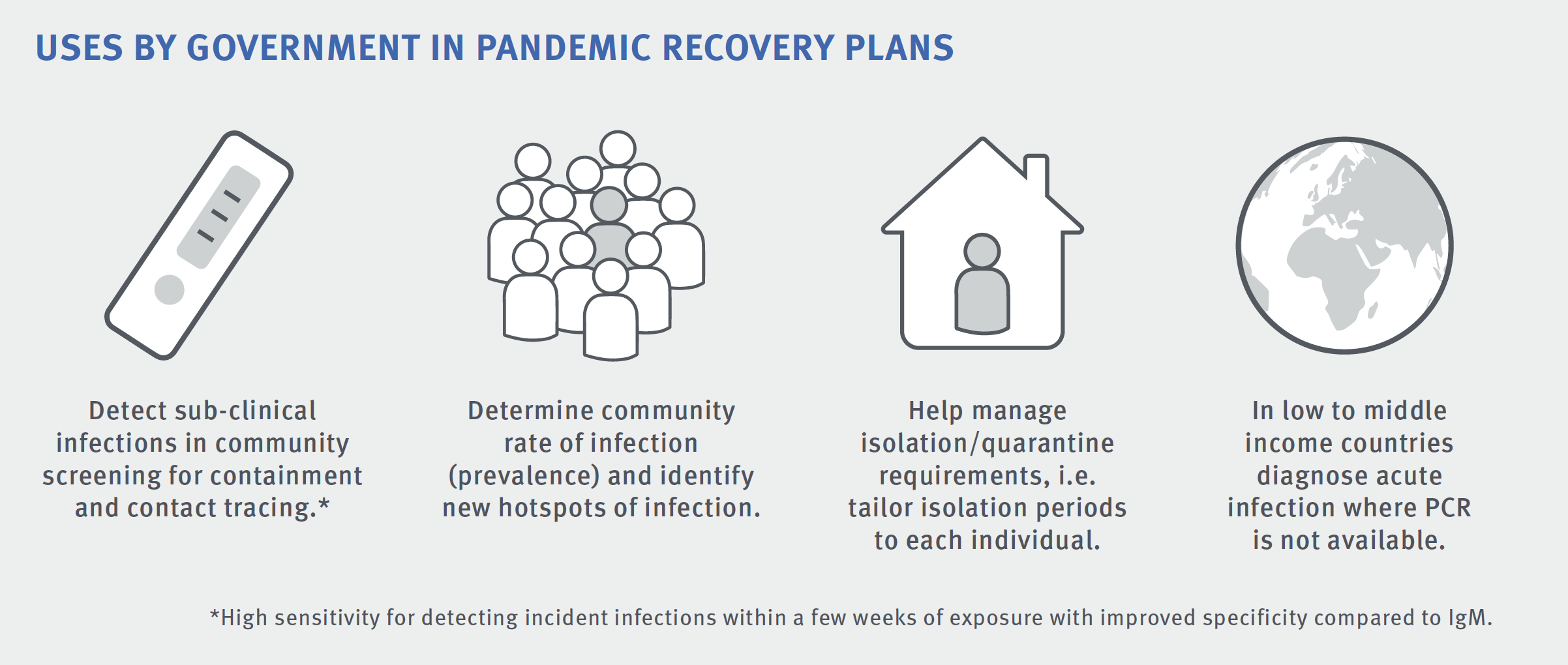

The best option for a testing blitz would be to use the RPOC test and the familiar PCR laboratory test, using throat and nasal swabs, in tandem. Because the RPOC test doesn’t require a lab, it can give a result within half an hour, and it can be used in settings where a lab-based test isn’t feasible. It can also detect whether a person has had COVID-19 over a much longer time period, whereas the laboratory test relies on catching people when they’re at the peak of their infection period.

“This test is probably most important in identifying contacts and asymptomatic cases,” Associate Professor Anderson said.

“The test can identify people who are very recently infected, enabling a closer look at their contacts.

“There is currently no way of telling where that person got their infection from, unless they’re from a known cluster.”

IDENTIFYING PEOPLE WHO HAVE CLEARED THE VIRUS

Containing Victoria’s second COVID-19 wave in mid-2020 was difficult, and the source of nearly half the cases during that time eluded authorities. The RPOC test would have allowed for backward contact tracing, which is a real missing link in the response to new infections.

“So, if you were just positively diagnosed, we currently try and figure out which of your 20 possible contacts you got it (COVID-19) from,” he said. “This antibody test would allow you to go and test all of your contacts, and figure out who among them actually had the infection. And then you can go to all of their contacts to see who you didn’t have direct contact with, but other people they may have infected – who could be infectious right now without knowing it.”

The test will also identify people who have been infected and cleared the virus, potentially enabling them to safely return to work post-infection. This will be vital for key services, in particular health workers who are disproportionately exposed to infection.

Another major advantage of Burnet’s RPOC test, he said, would be its potential to help measure the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines once they are used in the community.

“No vaccine is 100 percent effective. If many people are immunised with a vaccine, it’s unfeasible to follow up 10,000 or 100,000 and test everyone by PCR once a week to see if they have had the virus despite being vaccinated. But with our RPOC test, you could do this with monthly testing, for example.”

BURNET’S CUTTING-EDGE RESEARCH ENVIRONMENT

Associate Professor Anderson credited the research environment at Burnet for many of the discoveries he’s made. The Institute’s focus, he said, is on identifying and addressing “unmet medical needs” and getting products to market to translate research into positive health outcomes.

“There’s a phrase we use to describe what we’re doing: the minimum viable product. MVP. What characteristics of a test would make it good enough that it could be useful?”

That’s what his team are hoping to turn a prototype into. It took eight years to get a RPOC test onto the market for hepatitis E, and five years for the CD4 HIV test. But this time, Associate Professor Anderson is optimistic the new COVID-19 test can be fast-tracked.

Burnet’s diagnostic development received initial funding from the Victorian Government.

Please donate to support Burnet's COVID-19 response.